I Scream, You Scream: Italian Peddlers and Coal Miners

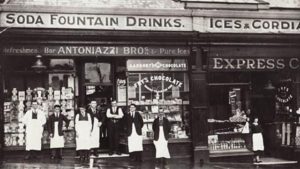

“We’re from the family that came over to make ice cream and run cafés,” the newly elected Welsh MP, Tonia Antoniazzi, told the magazine interviewer in 2017. “There are still Antoniazzi cafés all over Wales,” she exulted. Ms. Antoniazzi’s grandfather was part of a wave of Italian immigrants that flowed into South Wales in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They opened cafés and peddled ice cream in the towns of the industrializing valleys and in coastal communities of the region. “The greatest concentration of Italian cafés outside of Italy is in Wales,” journalist Pamela Petro observed in 1990. Convivial cafés owned by families with names like Chiappa, Rabaiotti, and Conti offered refreshment and a haven for the Welsh working classes.

The immigrants, single young men in the beginning, mostly hailed from the mountainous area around the hill town of Bardi, near Parma in the region of Emilia Romagna. By the time the villagers began their journeys from the Ceno valley, the once-fortified town with a grand 9th century castle had lost its prosperity and vitality. Peasants, tenant farmers, and small tradesmen—carpenters, cobblers, and other skilled workers—were barely managing to eke out a living in the harsh agrarian economy. To the Bardigiani, as the area’s dwellers were called, emigration seemed a surefire solution to their predicament. Their goal was to secure some kind of self-employment, however modest. They cherished their once secure independence and yearned to reclaim it. The newcomers, with their agricultural background, possessed an aptitude for small business. The assets they brought with them were similar to those anthropologist Robin Palmer ascribes to another group of entrepreneurially minded Italians in Britain: “The skills required in running a snack bar in London are not dissimilar to those of successful peasant farming.”

How did the Bardi villagers end up in Wales, and how did they come to pioneer the ice cream trade? A tantalizing clue lies in the story of Giacomo Bracchi, who broke the ground for the café business. Welsh historian Colin Hughes unearthed the details of this mythic figure’s career. Bracchi, he found out after digging through census returns, had left Grezzo, a small community just up the hill from Bardi, and arrived in London in 1881. He initially made his living as an organ grinder, a popular Italian vocation. The young man shared a crowded lodging house with other street musicians with distinctive Bardi names—Fulgoni, Sidoli, Zanelli. Located on 1-2 Robin Hood Lane, the house was in the central London district of Holborn, home to a growing Italian colony. The dwelling’s manager was listed by the census enumerator as Francesco Rabbajotti [probably Rabbaiotti]. He, Hughes points out, was the padrone (master) of the organ grinders, who are listed as his servants.

The twenty-year-old Bracchi, the historian surmised, stashed away enough funds to travel to Wales sometime between 1881 and 1893. Then in the 1890s, after possibly working in a coal mine for a short time, he opened the first Italian café and ice cream shop in the country. The occupation listed on his birth certificate, “confectioner,” belied Bracchi’s humble calling.

A smattering of Italians, largely sailors, already lived in Wales. The subsequent influx of Bardigiani would help build a larger colony, knit together by common origins and family ties—most residents of Bardi would come to have relatives in Wales. The success of innovators like Bracchi encouraged other aspiring entrepreneurs to follow their path.

For many of them, Wales was not their first resting place. Like Bracchi, they may have saved enough from jobs as chestnut sellers, street musicians in London, and other jobs for a nest egg to finance a future business. The necessary capital for the early trade, Hughes points out, was within the reach of the newcomers. A new trader might run his business from the back of his house and squeak by on fuel for his café stove from the abundant, cheap coal nearby. Some would begin their ventures with a simple hand cart to sell ice cream and later move up to a horse and wagon.

Guiseppi Bracchi built a small empire. At its height, he operated a chain of nine shops. The ice cream promoter’s fame was such that Italian cafés were often called “Bracchis.” His example was contagiousclusters of shops created by other enterprising families sprang up in the valley of South Wales. Kinship connections were, as they were for Bracchi, central to their prosperity. An owner based in Bardi might send each of his brothers to spend a year to manage the family business.

The immigrant risk takers also depended on the increasingly thriving Welsh economy for their success. Iron, steel, tinplate, and, most crucially, coal transformed once desolate valleys. Coal, which stoked the region’s industrial engine, accounted for one-third of the world’s exports of the commodity between 1890 and 1910, historian Hughes notes. A network of railways and port facilities helped fuel the boom.

The burgeoning industry needed willing hands. The valleys were now teeming with people desperate for work. Writer Thomas Jones captures the social upheaval: “They came from distant rural areas on foot and in carts, they came as Christians and pagans, thrifty and profligate, clean and dirty; and gradually sorted themselves out in their new surroundings according to tradition and habit. . . . The empty valley was turned into a long trough full of human beings bustling and jostling each other for food and drink.” The flourishing Welsh economy only heightened the strong desire of the Bardigiani to emigrate. The surging industrial workforce created a market for the services the hospitable Bracchi cafés could offer.

What were these early shops like? The Alien Land, a novel discovered by historian Hughes, depicts a 1902 café, owned by a Giusseppe Marti, a character based on Giacomo Bracchi. Angelo, a young boy recently recruited to work at the business, peers at his new workplace: “There were glass shelves behind the counter and arranged upon the shelves were glasses and bottles of various colours and lines of china cups. Below the shelves were boxes containing multi-coloured sweets and alongside them other boxes placed upright to display the packets of cigarettes inside them. Towards the middle of the counter was a glass case containing cakes, some iced and some filled with cream. . . . At the far end of the counter, as far away from the over-heated stove as it was possible to get, was an ice-cream container, a highly-coloured cabinet with a lid like a French sailor’s cap in the middle of it.”

To survive, the cafés needed a steady flow of youngsters like Angelo to keep them running. Proprietors tapped into the webs of friends and relations back home to enlist helpers. Bracchi himself often journeyed to Bardi searching for prospects. “Giacomo Bracchi used to go to Bardi to the market, and people with young boys would say, ‘Mr. Bracchi, would you like to have my boy to work for you? Take him to England,’” the son of a merchant from Bardi recalls in a radio interview quoted by historian Hughes. “All right, 30 shillings a month and I’ll give them clothing, feed them, and look after them,” Bracchi would say. “He used to go to over there and bring back about 10 to 15 boys over.”

Convincing families to send their sons was not a hard sell: A reputable businessman with roots in the community could be trusted to look after their child. It was also not unusual in Bardi for families to send their boys abroad. The master or his agent sweetened the deal with a small payment to their parents and a promise of room and board to their boys. (They usually lived under the same roof as their employer.) The setup was a variation on the padrone system, an arrangement in which bosses recruited industrious workers by shrewdly cultivating ties to their families.

Stories of successful Bardigiani who had traveled to Wales to try their luck excited the ambitions of village youth. In Bracchi, a musical written by Emyr Edwards, Grandpa Bracchi talked with Emilio, a boy eager to strike it rich in a faraway land. In the musical, which caught the attention of scholar Bruna Chezzi, the old man spins an alluring picture of the mysterious and bountiful country:

GRANDPA BRACCHI: You see, Emilio, the life here in the mountains of the Emilia Romagna is very hard for you and me.

EMILIO: Grandpapa Bracchi, Papa says that there is gold at the other end of the rainbow. . . . Far away in other lands? . . . In France and in England?

GRANDPA BRACCHI: And in Wales.

EMILIO: Wales? Where’s that?

GRANDPA BRACCHI: The other side of England, where there’s treasure in the ground. And men dig it up.

EMILIO: Treasure?

GRANDPA BRACCHI: Black gold. They call it coal.

EMILIO: Is there a fortune for everybody there, grandpapa?

GRANDPA BRACCHI: That’s where your uncle Alonso went, to open a café, and to sell ice cream.

EMILIO: That’s where I’m going one day, grandpapa. To Wales to earn a fortune.

For all the inducements, the work of the apprentices was grueling. Their daily toil was severe, although it was tempered by their parents’ connections to their bosses. Nevertheless, they labored under a “stern and often harsh regime,” Colin Hughes argues. They were expected to spend long hours pushing a cart or wheeling a barrow vending ice cream through the streets. After summer was over, they were required to peddle fish and chips, another niche the Italian merchants carved out. The owners expected no less from their workers than they had from themselves. “They had themselves worked hard for long hours and had known privation,” Hughes points out. “They had no compunction about imposing similar conditions on their employees.” Many of the lads chafed under these constraints but put up with them. After learning the ropes, they left as soon as they could, often to start businesses of their own.

In addition to their street trade, the Bardigianis ran a lively café business. Quick meals like beans on toast, cigarettes, candy, tea, and oxo (a hot drink made from beef bouillon cubes) helped create an enthusiastic following. Coffee would only later become a mainstay of these shops.

The Italian ventures are reminiscent of pioneering Greek immigrant food businesses in America. In the streets, lunchrooms, and diners, the Greeks were purveyors of inexpensive, filling food. Rather than specializing in their own cuisine, both groups largely catered to the tastes of workers in industrializing towns and cities in the early 20th century. Outside factory gates in Chicago, Greek vendors hawked “red hots” (hot dogs) from pushcarts and lunch wagons. In their cafés, Italian merchants in Wales served pork pies to mine and iron mill workers. The traders came from similar backgrounds. Starting out as peasant villagers, they emigrated from struggling rural areas to set up shop in growing towns and cities.

Ice cream, a major draw of these cafés, was a less familiar—and even exotic—product. Inheritors of a long tradition of ice cream making by Italians, the merchants from Bardi were introducing the confection, once the province of the wealthy and titled, to commoners in Wales. Families worked together in the early Bracchis cranking out ice cream with hand-operated machines. The elegant treat was once served in silver dishes in posh cafés in Italy and France, often by Italian proprietors. In the early 1800s, Giuseppe Tortoni, a glacier (ice cream maker) from Naples, ran a café on Paris’s Boulevard des Italiens that sold this and other luxurious refreshments. His guests included such notables as Talleyrand, Metternich, and Baron de Rothschild.

In the end, it was not their products that endeared the shops to the Welsh. It was their infectious atmosphere. “The Italians had hit on a recipe for success in the thriving valleys,” Colin Hughes remarked. “The local population, crowded in their mean-built houses, had few civic amenities. Here was a home away from home, a social gathering place where there was no obligation to buy the wares, however long you stayed.” Later, the historian observed, “they gave particularly to the young, single working man a service, which the Welsh themselves, by their temperament would never have provided. The Italians brought a certain elan.”

Keen merchandisers, the café owners adapted their businesses to a culture quite alien from their own. Since many of the Welsh were “Non-Conformists,” Methodists who were temperance adherents, it was risky to offend them. After Wales passed a Sunday Closing Law in 1881, the Italians spotted an opening in the market. They started calling their shops Temperance Bars in order to lure workers and their families who might previously have gone to the now shuttered pubs. During the week, these homey establishments even attracted “punters” away from the public houses. Business was good enough that proprietors were willing to pay the fines occasionally meted out by strict law enforcers. A strong bond developed between the unlikely partners, between chapel goers and Laborites, on the one hand, and immigrants who were, as writer Peter Dunn described them, “devoutly Catholic and discreetly Tory.”

The Italian cafés gained momentum and the outsiders won acceptance. Their number mushroomed—more than three hundred of these businesses were operating by the mid-1930s. Single men married and the Bracchis were transformed into family enterprises. As more relatives arrived from Bardi, a tightly knit community emerged. Immigrants who came with little means gradually achieved relative affluence.

Over time, however, conditions became less fertile for the shops. Industries like coal and steel, which helped the cafés rise, began to decline. Television and other forms of entertainment ate into their business, especially the evening trade. Some ethnics moved into more lucrative sections of the industry, opening trattorias serving Italian food or other full-service establishments. For example, the Berni family, prominent in the ice cream business, built a popular chain of steakhouses. Children of Bracchi owners and young people generally were reluctant to follow the entrepreneurs into the café business. White collar jobs had more appeal to the second and third generations, especially to college goers.

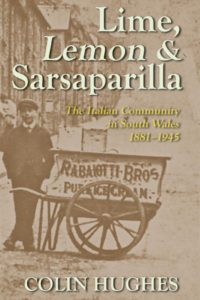

Colin Hughes, who wrote so lyrically of the glory days of the immigrant cafés in his book, Lime, Lemon, and Sarsaparilla, sounded a gloomy note in 1991, the year of its publication. The once vibrant business was withering away, shops were closing, and “Chinese takeaways are moving in.”

Through all the ups and downs of the ice cream business, the Bardigiani kept up strong connections to their homes in the Como Valley. The longer they lived in Wales, it seemed, the more these ties strengthened. Rather than shed their traditions, they accentuated them. “My dad says the Welsh-Italians are almost more Italian than the Italians,” Emilia, a postgraduate broadcast student told journalist Amanda Powell, writing in Cardiff’s Western Mail.

Homesick Italians made regular visits to Bardi. Some bought houses in the area. “It’s strange, you’ll be in this little town in Italy and you’ll hear Valleys accents,” student Emilia commented. During the summer in Bardi, Colin Hughes noted, “spoken English, heavily accented, mingled with dialect Italian in the square. Cars with Great Britain plates are everywhere, among them an occasional Rolls Royce.” An annual festival, which features dancing, traditional songs, old-time food, and other festivities, encourages summer journeys. To the consternation of the visitors, the locals are not always welcoming. A popular image of the sojourners, Hughes says, is that they have been “abroad” and “picked up money with a shovel.” The fondness their Welsh hosts felt for the Bardigiani should assuage any hurt feelings.

NOTE: Colin Hughes’s fascinating book, Lime, Lemon, and Sarsaparilla, was an invaluable source for me. Any quotations not otherwise identified come from that volume. Another important reference is Lucio Sponza’s Italian Immigrants in Nineteenth-Century Britain.