“Yes, AOC, DC Does Have a Bodega Culture…,” the Washington Post proclaimed. The New York City representative had been lamenting the absence of these New York City corner shops in her new home. Increasing references to bodegas in Washington were getting tiresome. Wasn’t this neighborhood gathering place a quintessentially New York City institution? Why did DC even have to lay claim to it? Was the Capital City developing an inferiority complex?

Bodega had filtered into the popular lexicon. People were using it casually as a catchall term for quick food convenience stores, whatever their lineage. What sense did it make, for example, to dub a Korean grocery store a bodega? Using the expression conveyed a certain worldly acquaintance with what had once been a marginal outlet—at least marginal to these onlookers.

New York politicians now must pay homage to the bodega, just as previous campaigners had paid mandatory visits to a knish bakery. God forbid that a vote seeker would mistake another type of store for the real thing. During the recent New York City Mayor’s race, Andrew Yang committed this blunder. He saluted a grocery, more like a sanitized Whole Foods, where he bought a banana and a bottled tea as a “bodega.” He was roundly chastised for his error.

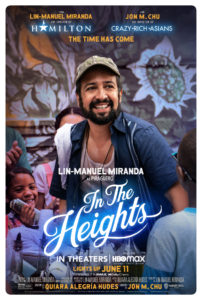

The bodega was coming out of the shadows. The HBO adaptation of “In the Heights,” a Broadway musical created by Lin-Manuel Miranda, celebrated this neighborhood fixture. Set in Washington Heights, a predominantly Dominican section in New York City, the show revolved around a Latin store and its young Dominican owner, torn between his ties to his community and his longing to return home. The mock bodega featured props like the red and yellow cans of Café Bustelo, the strong Cuban coffee, which had become popular in hip circles.

The bodegas I knew were shops, owned largely by Dominicans. First established in Latin immigrant neighborhoods, they now dotted many corners of the New York metropolitan area. They still serve Hispanic regulars, cash their checks, give credit and share news and gossip. As young urbanites moved into the city, they discovered the bodega. It is a handy place to buy egg and cheese rolls, coffee, and other daily necessities.

Immigrants from Puerto Rico pioneered the bodegas in New York City. The proprietors were part of a large wave of islanders who descended on the city after World War II. They built a colony in East Harlem, the barrio, as it was known, a neighborhood that had previously been settled by Irish, Germans, and Italians. Corner stores or bodegas, a name borrowed from the Spanish word for tavern or wine cellar, were haunts for immigrants first in East Harlem and later in the Bronx or Brooklyn. Owners sometimes set up a table outside for the locals to play dominos. The owner, or bodegerio, cared for customers’ everyday needs. “People come to a bodega when they want something small or quickthat’s our secret,” Albert Sabater, an owner told The New York Times’ Mariane Howe.

The owners needed business advice: what goods to stock and where to get them cheaply. A young go-getter, Prudencio Unanue, stepped in to help the budding enterprises. A native of Spain, who had migrated to Puerto Rico, he moved to New York City in 1918. Ten years later, he opened a small import business to bring food products from his homeland. His target was Spain’s large émigré community centered in the Manhattan neighborhood of Chelsea. The influx of Puerto Ricans convinced him that there was a larger market to tap. Unanue called his venture Goya.

The new arrivals were a different breed from the Iberians. They were “one of the first groups to migrate in masses,” Gerard Colon, Goya’s marketing director, recounted. The company built a food packing plant in Puerto Rico. The island pipeline provided the immigrants with products that “reminded them of home,” Unanue’s son, Joseph, recalled.

Goya cultivated the bodegas. “In the ’50s, we sold only to bodegas. The bodegas created us,” Joseph Unanue said. Goya’s wide array of goods filled the stores’ shelves: rice and beans, boxes of dried salt cod, amber bottles of guava, coconut, and tamarind syrups to make tropical drinks, papaya and guava preserves, and glass jars of black pepper, cumin, sesame seeds, and other spices.

The bodega would change hands. A new immigrant group, the Dominicans, was streaming into “Nuevo Yorko,” as they called it. The more than 500,000 Caribbeans became one of the city’s fastest growing groups. As the Puerto Ricans left their businesses, Dominicans, from the early sixties to the eighties, filled the void. “They started retiring and their kids were going into the professional world,” Luis Salcedo, the Dominican-born director of the National Supermarket Association, said. The Dominicans modeled their businesses after their homeland’s convivial markets, or colmadas.

Government workers, cab drivers, cooks, and factory hands from the island provided a strong customer base for the Dominican bodega’s wares. Goya’s salesmen again provided wise counsel. “They are very loyal customers to our products,” Goya executive Conrad Colon pointed out.

Both the Puerto Ricans and the Dominicans shared common tastes. “The basic thing is the olive oil, garlic, and oregano,” Colon noted. Each group also had particular preferences, and Goya tailored its product line accordingly. Puerto Ricans favored pink (rosada) and kidney (marca diabla) beans, while the Dominicans were enamored of the red roman or cranberry bean.

The bodegas spread out to Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania. The entrepreneurs, for example, found an opening for their businesses in Waterbury, an old industrial town in Connecticut’s Brass Valley, where the Irish, Italians, and other early immigrants had settled.

The bodega business in now in flux. Even though Dominicans still hold a commanding position in the market, new ethnics have been attracted by the business opportunities. Yemeni immigrants are now the most visible of the new recruits in New York City. In Brooklyn, where they have taken the helm of many corner shops, the change is striking. “Lamb over rice is on offer at my local Yemeni owned bodega,” writer Quizayra Gonzalez observes.

Yemenis have a long immigrant history in America. They initially labored in auto plants in Detroit and steel mills in Buffalo. Weary of toiling in declining industries, they turned to small business. “By culture, we are traders,” Abdul Nashir, principal of an Islamic school in Lackawanna, a town next to Buffalo, remarked. On Buffalo’s east side, the Buffalo News reports, Yemeni shops have sprung up “to sell everything from frozen meats and bread to scented body oils and winter jackets and gloves.” The immigrants have followed a similar route in other cities. Yemenis control Oakland, California’s liquor business and operate many convenience stores in the Detroit area.

Yemenis, some of whom fled Buffalo’s steel mills, have joined a community of Arab merchants in downtown Brooklyn. “Every kid back in our town in Yemen knows the names ‘Court Street’ and ‘Atlantic Avenue,’” Ibrahim Qatabi, a Yemeni activist, told Christina Goldbaum of The New York Times. Owners often hired relatives who, after learning the ropes, were eager to start their own shops.

The tight kinship ties in the Arab state encouraged the patronage relationship. “Yemeni society as a whole is structured far more along clan society- and clan-based lines than any of the other Arab countries, Moustafa Bayoumi, a Brooklyn College professor, told Kiran Sury, a City Limits writer. Proprietors maintain their family connections in Yemen, sending back funds. “They also want to keep very much a foundation within Yemen because it’s a very remittance based economy,” Bayoumi added. “And so people tend to go back and forth a lot.”

The storekeepers, who prefer to call their shops delis or convenience stores rather than bodegas, carry products similar to those in Latin stores. The stores, however, may have a prayer room in the basement, and only sell halal meats, not pork.

The owners have banded together to form the Yemeni American Merchant Association. The organization caught The New York Times’ attention in 2019, when it protested President Trump’s travel ban by closing their shops and gathering for a rally in downtown Brooklyn. The President’s order hit home. It threatened to stop Yemeni wives and children from reuniting with their families.

The owners are picking up American merchandising techniques. Ahmed Alwan, a bodega merchant, made a Tik Tok video showing him playing a math game with a customer. As reporter Quizayra Gonzalez tells it, the owner offered a prize, any item in the store, for a correct answer. The patron guesses right and reaches out to grab the one indispensable item in any bodega. Alwan quips, “Not my cat.” Some second generation Yemenis are eager to remake their parents’ bodega. One owner’s sons, The Los Angeles Times reports, prodded him to expand his wares to include “fresh squeezed juices, fruit shakes and organic breads.” Their father was adamant. He was comfortable with the store as is.