Roaming the web recently, I made a discovery, one that sheds light on the marriage between immigrants and fruit peddling. I had always assumed that the popular song, “Yes, We Have No Bananas,” was written about an Italian hawking fruit. I was wrong.

Sheet Music for “Yes, We Have No Bananas”

Thanks to Harry Karapalides and the Philly Greek-Style Blog for the revelation that the line came from a hit song released on March 23, 1933. The song, titled with that inimitable line, was composed by Frank Silver and Irving Cohn and later recorded by Benny Goodman, Jimmy Durante, Louis Prima, and

Spike Jones and his City Slickers. The peddler celebrated in the song was actually Greek.

Silver got the idea for the song from an encounter with a Greek fruit vendor. Silver, whose orchestra was playing at the Long Island Hotel, passed his stand every night. When the musician asked if he had bananas, his response was invariably, “Yessss, we have no bananas.” (Bananas were scarce because the Central American fruit then was riddled with disease.)

The line was so catchy that Silver felt impelled to write a song. “The jingle of his idiom haunted me,” the song writer recalled. The song’s first verse went like this:

There’s a fruit store on our street,

It’s run by a Greek,

And he keeps good things to eat,

But you should hear him speak!

When you ask him anything, he never answers “no.”

He just “yes”es you to death, and as he takes your dough,

He tells you,

Yes, we have no bananas.

Its chorus is memorable:

Yes, we have no bananas. We have-a no bananas today.

We’ve string beans, and onions, cabbageses and scallions,

And all sorts of fruit and say

We have an old fashioned to-mah-to. A Long Island po-tah-to,

But yes, we have no bananas. We have no bananas today.

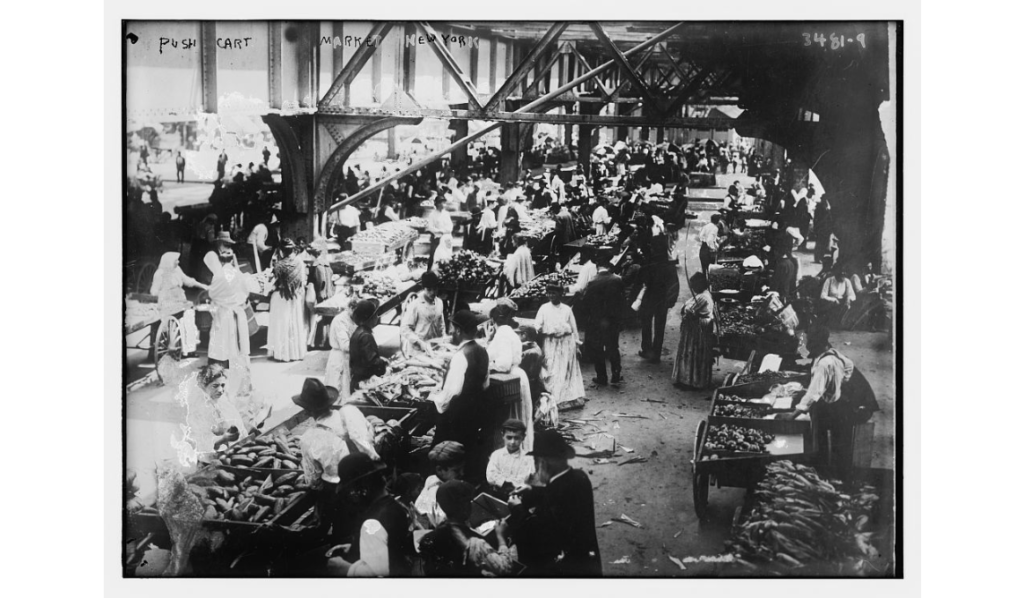

Street vending, especially peddling fruit, was a handy occupation for the immigrant greenhorn. According to some estimates, 2,000 Greeks in Chicago were peddling produce in 1911. Looking for help, a fruit merchant would take on a kinsman for a job that required little English and required short encounters with customers.

Greek Diner Owner

Peddling was also a stepping stone, a way to climb the job ladder. With savings, experience, and a sponsor, the vendor might improve his lot. He might move up, starting a small business—perhaps a hot dog stand, a lunchroom, or a shoeshine parlor. Many Greek newcomers chose this route.

Peter Bonduris, a New York City fruit peddler, funneled his kinsmen into jobs in Birmingham, Alabama, which had a large Greek enclave, after they had learned the ropes of his business.

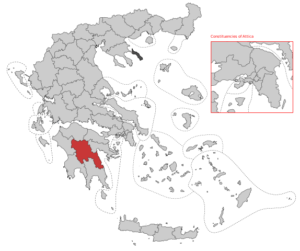

The Arcadian Region of Greece, Where the Village of Pelata Is Located

Over time, the new hand would pick up many of the habits, idiosyncrasies, and cultural nuances that could be learned in no other way. One of Peter Bonduris’s hires was John N. Bonduris, who came from Pelata, the same village in the Peloponnesus. John, who knew few words of English, had the same response to every customer’s question: “I don’t know and 10 cents a bunch.”

The Greek vendor was the purveyor of a fruit that was still novel and even forbidding. Some Americans worried that the fruit might be hard to digest and might upset their stomach. People also worried about a fruit sold on the street. The Literary Digest assured its readers that the fruit’s wrapper kept them “uncontaminated by dirt and germs, even if purchased from the pushcart in our congested streets.”

Push Cart Market, New York, Circa 1910-1915. Bain News Service

The immigrant peddler secured a place in American folklore. The mirth of “Yes, We Have No Bananas,” however, obscured the harshness of the vocation.

The peddler was often the victim of hostile prejudice. The Chicago Tribune heaped scorn on them: “Nearly every banana peddler in this city is a Greek. They herd together by the dozen, and have a head man who does all the buying, and usually drives a close bargain for a few banana bunches. The Greeks are of a very jealous disposition and believe all women are faithless. So they never marry in this country. They are filthy, shrewd, and of a low order intellectually. The profits of the day’s peddling are always divided equally among the company, and in this way they may be said to operate a small sized banana trust. They are born traders and carry on a profitable business, considering their daily expenses do not average more than 10 cents a day.”

Business groups pressed the city to stop the threat. In 1904, the Chicago Grocers Association urged the City Council to prohibit hawkers from peddling in alleys and streets.

Bananas

The Greeks also had to fend off rivals bent on stealing their business. In Chicago, Greeks and Italians battled for control: “… the Greeks have almost run the Italians out of the fruit business not only in a small retail way, but as wholesalers as well,” the Chicago Tribune declared in 1895. “As a result, there is a bitter feud between these two races, as deeply seated as the enmity that engendered the Graeco-Roman Wars.”

Despite the animosity, the immigrants were admired for their ambition and entrepreneurial drive: “… the Greek will not work at hard manual labor like digging sewers, carrying the hod, or building railways,” the same newspaper observed two years later. “He is either an artist or a merchant, generally the latter.”

Frustrated with their lowly status, the Greeks yearned for economic independence. These were not idle dreams. Many Greek street merchants pulled themselves up. In Chicago and other cities, they carved out a niche in the restaurant business. By 1913, according to sociologist Charles Moskos, there were at least 600 Greek-owned eateries in Chicago. Instead of peddling bananas, they were taking orders for coffee, hot dogs, and pie.